The value of medicines

Medicines do so much more than help patients treated today. Accounting for a drug's societal value reveals that medicines are worth a lot more than some give them credit for.

Medicines don’t just help those who take them today.

Turns out that when you take the societal perspective into account using the broader math represented by “the value flower,” medicines are worth a lot more than some give them credit for.

Elements of Value:

-

Medicines improve the quality of life of caregivers, letting everyone be more productive, and they reassure all of us when we're healthy because we know a medicine exists if we need it (risk reduction).

-

Ultimately, medicines will become generic, inexpensive treatments that continue to benefit society and an increasing number of patients (population growth). At the same time, cheap generic medicines combat rising healthcare costs (dynamic net health system costs).

-

They save patients and caregivers from the financial and mental burden associated with hospital visits (direct non-medical costs). Effective medicines also preserve limited resources and capacity that may help other patients (community spillover).

-

Even seemingly small benefits can have an outsized impact on the lives of patients depending on disease severity.

-

A medicine can also have unintended benefits or inspire ideas for how to develop other medicines (scientific spillover).

Some health economists overlook these elements of value.

Today, many health economists still rely on outdated "cost-effectiveness analysis" (CEA) to assess a drug's value and whether it's worth its price. By ignoring all the petals of the "value flower" or only including a few, CEAs underestimate the value of a medicine to society. These over-simplified analyses argue that, at their prices, some medicines weren't worth inventing. Insurers then use this simplistic math to deny coverage and/or charge high co-pays, even for life-saving treatments, deterring their appropriate use and signaling to investors that society doesn’t want more such medicines, even though they actually are desired by patients and actually cost-effective for society (if you do the right math).

When valuable new medicines are undervalued, we get fewer of them, and we all end up worse off.

Let’s not undervalue new medicines.

In calculating whether a medicine may be worth its price, “generalized cost-effectiveness analysis” (GCEA) includes more of the elements of value that conventional CEA ignores, showing that medicines are much more "worth it" than simple CEA may suggest.

And when the math shows that a drug is well worth its price to society, we should be able to count on insurance to make it affordable to the patients who need it, which means offering it with low out-of-pocket costs, so that we are all paying for it together out of premiums — that's NPLB's mission.

GCEA asks a broader set of questions that more fully capture the value of a medicine:

What will the savings be when this drug goes generic?

Will this drug ease the burden on caregivers?

Does this drug benefit healthy people by lowering everyone's risk?

and many more…

See how the math adds up.

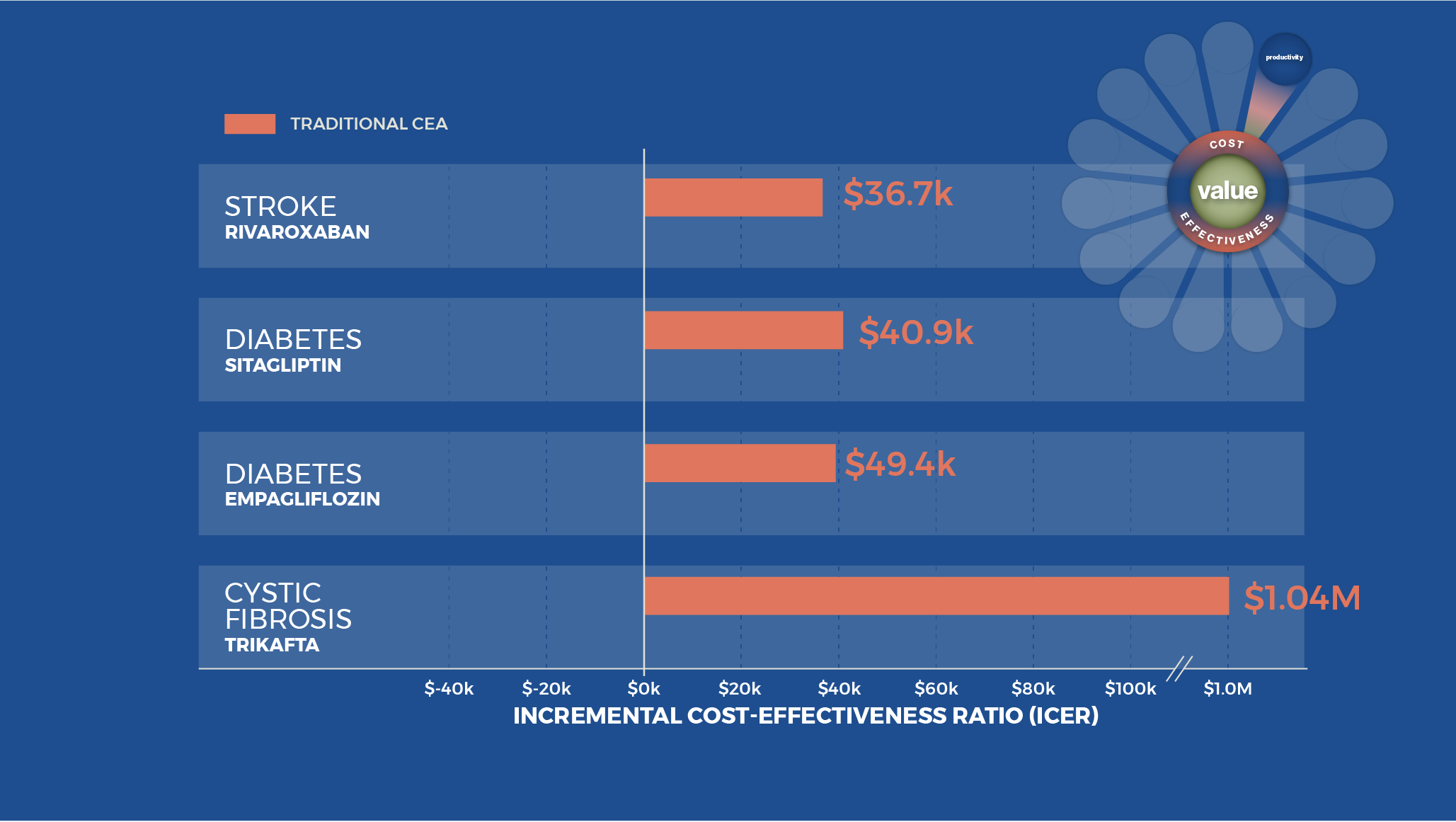

CEAs attempt to quantify how much value medicines provide for their price.

This ratio is the cost for each measurable improvement in health. A lower ICER value means a drug is more cost-effective and therefore offers better value for society.

But the benefits traditional CEAs measure are narrow.

They typically only capture the benefit to patients taking the medicine today and ignore the societal impact like the benefits for caregivers and the savings once a drug goes generic.

When economists consider even a few elements of societal value, they found that traditional CEAs substantially miscalculate how worthwhile medicines are. They were bargains!

Some are even cost-saving (negative ICER value)!

Insurers sometimes use this over-simplified math to deny coverage for life-saving treatments, which harms patients today and signals disinterest in more such medicines, turning investors off from funding their discovery and development.

When we undervalue new medicines, we get fewer of them, and society ends up worse off.

RELATED RESOURCES

Valuing the Societal Impact of Medicines and Other Health Technologies: A User Guide to Current Best Practices

A new paper published in Forum for Health Economics & Policy by twelve leading health economists explains why the conventional math used to value medicines falls short, and it lays out a consensus “user’s guide” for operationalizing overlooked elements of societal value.

We’re building support across the biotech ecosystem

BECOME A FIRST RESPONDER & THOUGHT PARTNER

Sign up to receive action alerts. Help protect access to lifesaving medicines & preserve innovation for those still waiting for a cure.